CUDA basics

General purpose processing on graphics processing units (GPGPU) have gained a huge interest within past decades. GPGPU relies on CPU deciding to delegate heavy arithmetic and parallel work to GPU. This more and more common type of task is hardly done by CPU. Having GPU already among nearly all servers and laptops avoids creating and introducing new specific and costly hardware component for some applications. GPGPU is therefore a solid solution to apply and to probe.

CUDA

As the name suggests, GPU used to be designed for graphic processing. This component has been upgraded through years to answer the constant growing need of video games. Consequently, a graphical domain approach was the only perspective to program a GPU with dedicated tools like OpenGL or Microsoft Direct3D. Thus, some requirements for general purpose programming were missing like integer representations of the data, logical instructions, etc… To fill this gap, Nvidia has developed CUDA (Compute Unified Device Architecture) to fully exploit all Nvidia’s GPUs potential.

Other solutions exist, like CTM (Close to Metal) from AMD and a proprietary free one called OpenCL. But CUDA has several assets on its own. First of all is CUDA’s owning company: Nvidia’s GPUs hold the most part of the market. Developping on the most widespread component - in term of discrete GPU [1] - is an obvious advantage. Furthermore, CUDA is the subject of an active and constant support by both Nvidia and the community. We can find a tremendous amount of knowledge and help about any issue. Finally, as both the GPUs and the API to program them are developped by the same company, we generally observe better performance [2]. Furthermore, CUDA developpers will introduce new concepts alongside latest deeply known hardware. But the main drawback about CUDA is the proprietary aspect. Even with the best will, we can’t obtain every details of how GPUs and CUDA really work. Despite that, CUDA is still a powerfull and valuable application programming interface (API) that works with several languages such as C, C++ and Fortran.

This post will present the basic aspects of CUDA and concepts to be aware of. First we will introduce the programmer point view, meaning the concepts that we can use in our code with CUDA API. Then, we will confront that view to the hardware reality and what it really does. Finally we will highlight the key role of memories in CUDA by matching the programmer view with memories and by presenting the global GPU architecture around memories.

Basic Concepts

In CUDA, it’s important to notice that we are programming with two major components: the CPU also called host and the GPU aka the device. All the code will be passed by the host which also allocates then transfers all needed data to the device. Finally, the host will launch the device code aka kernel code through its function name call.

Compute capability (CC)

CUDA is an evolving API that has started in 2007 and has evolved as GPUs do with more and more functionnalities through years. Due to backward compatibility, CUDA has introduced an attribute on all different GPU’s series to inform about the device capacity to achieve certain CUDA functionalities. This attribute has been called compute capability. Its value impacts the behavior of some basic concepts or architectural functionalities and even given reference values.

Currently, this post is written in a project context working with a Jetson TX2 and a 6.2 CC. As a consequence, concepts and values are more specific to our CC architecture. For further informations and details, check the Nvidia CUDA C programming guide.

Programmer view

Following notions are the ones manipulated in our code. We’ve decided to take a top-down approach.

Kernel

The kernel is the parallel code launched through the host on the device. The kernel code (defined with the __global__ declaration specifier) is called in the host main function. This call has to be done with two parameters expressing together the total amount of threads wanted to execute the kernel code in parallel. The syntax is:

__global__ kernelFunctionName(arg1, arg2, ..., arg n){

//Find the thread's ID which is executing the kernel code

int i = threadIdx.x;

//Kernel code to excute

....

....

}

int main(int argc, char * argv[]) {

//host code containing also device memory allocation and transfer

....

....

//Lauching the kernel code

dim3 Grid(10, 5, 1); //Grid definition with x, y and z dimensions respectively 10, 5 and 1.

dim3 ThreadsPerBlock(50); // Block definition with x, y and z respectively 50, 1 and 1 (y and z equal to 1 if not given).

kernelFunctionName<<<Grid,ThreadsPerBlock>>>(arg1, arg2, ..., arg n);

}

As we can see, the __global__ function - aka kernel - is launched by the main host code with the Grid and ThreadsPerBlock parameters. Those parameters can either be a dim3 structure as presented above or a simple int if we only want a 1-dimension parameter. The grid represents the total amount of blocks, each containing ThreadsPerBlock threads. The kernel code is thus run with ThreadsPerBlock*Grid threads separated equally in the grid blocks.

The kernel code is stored into the global memory (the device main memory) with a limited size corresponding to 512 million instructions. It will also use the device’s instruction memory caches.

A kernel code is always asynchronous with respect to the host code, and sometimes even regarding other device instructions according to the CC. In regards to that feature, the host code can take advantage of overlapping with the device.

cudaMemcpy(d_a, a, numBytes, cudaMemcpyHostToDevice); // Synchronous function, no overlapping allowed.

kernelFunctionName<<<Grid,ThreadsPerBlock>>>(arg1, arg2, ..., arg n); // Asynchronous, we can take advantage of overlapping.

//Host code during device execution

...

// End of the overlapped host code. Waiting for the end of the kernel execution to transfer data between the host and the device.

cudaMemcpy(a, d_a, numBytes, cudaMemcpyDeviceToHost); // Synchronous function, no overlapping allowed.

Grid

Created when a kernel in launched, the grid is composed of blocks. A grid can be either of 1, 2 or 3-dimension depending on the CC. Blocks in a grid contain each the exact same number of threads. Every block of a grid is executed in a total independent and parallel way. Thus, there are no synchronizations between these blocks and no dedicated communication means.

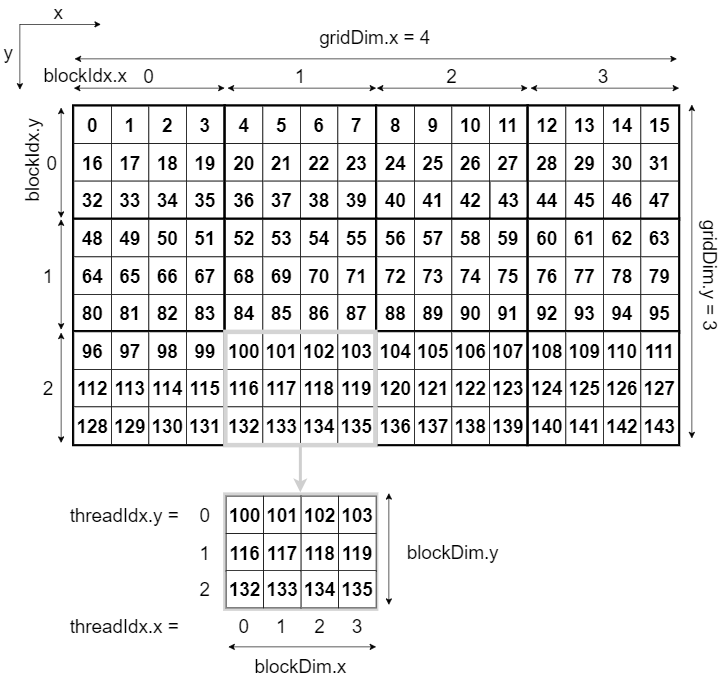

The size of a grid is limited to 65 535 blocks in each dimension except for x which is 2^31 - 1. The grid argument given in a kernel function call can either be a dim3 structure or a simple int. That way, we can decide specifically the grid we want as presented on the figure below.

In CUDA, the two reasons for choosing a multi-dimensional grid are: firstly to overtake the one-dimensional block size limitation and by extension the thread number limitation; and secondly to get a better representation of a potential multi dimensional problem resulting in an easier way to index data structures.

Blocks

A block is a group of threads in 1, 2 or 3 dimensions. These dimensions are set when launching the kernel with the ThreadsPerBlock argument. A block is composed of at most 1024 threads and thus dimensions (x,y and z) must verify: “xyz <= 1024”. Only x and y dimensions can handle 1024 threads. The z dimension is limited to 64 threads. A block consists of a group of dedicated resources - registers (32K at the maximum) and shared memory - and is executed concurrently with other blocks on a SM (Streaming Multiprocessor, further details below).

A block represents a group of threads that can easily synchronize and communicate. As a consequence, communications and synchronizations must be taken into account when sizing blocks.

Thread

The finest-grained concept for describing a parallel program is the thread. As explained, a thread is what will execute a kernel code in parallel. Each thread posesses its own local ID (local to its block) which can be used to split the data to treat between all the threads. For instance, if 4 threads - with IDs going from 0 to 3 - have to treat a N sized array then each thread could treat the data at indexes [N / 4 * ID; N / 4 * (ID + 1)[. The local ID is per dimension and it can be directly found with the CUDA API’s structure threadIdx. Based on the local ID, the global ID is defined considering all the threads in the launched grid. The global one depends on the grid configuration and is calculated as done in the below example.

__global__ kernelFunctionName(arg1, arg2, ..., arg n){

//Find the thread's id which is executing the kernel code.

//Local ID per dimension

int x = threadIdx.x; //1D component

int y = threadIdx.y; //2D component if exists

int z = threadIdx.z; //3D component if exists

//Linearized local ID

int tid_2D = blockDim.x*threadIdx.y + threadIdx.x; // Linearized local ID for a 2D block

//Global ID

int idx = blockIdx.x * blockDim.x + threadIdx.x; // x global ID in 1D

int idy = blockIdx.y * blockDim.y + threadIdx.y; // y global ID in 1D

int w = blockDim.x * gridDim.x; // Grid width

int global2D = y * w + x; // Global ID in 2D

//Kernel code to excute

....

....

}

NB : Threads and blocks IDs are in a column-major order with regard to warp organization (further details in the warp paragraph).

The above example highlight ways to obtain local and global IDs in 1D and 2D. Depending on the problem, a kernel code can entirely rely on local IDs (for instance if each block treat the whole data set) or just use global ones (if the data set is shared by all blocks). The one needed will only depends of the problem to solve, the kernel code’s structure and the grid architecture decided.

NB: Linearization which is the operations to obtain the thread ID as if there was only the x dimension (it’s the way to get the global ID) becomes more and more complicated as dimensions grow.

The following figure represents a 2D grid with 4x3 blocks of 4x3 threads and gives the global index for each threads.

Threads of a block run concurrently on the cores of a streaming multiprocessor (SM). A thread utilizes a part of its block’s resources. As general purpose registers inside a block are shared between threads, a tradeoff has to be found between parallelism (the number of threads) and efficiency of one thread, as less registers per thread means more code spilling (reads and writes in memory). The maximum number of registers per thread is 255, but bound values can be specified by the user to the Nvidia CUDA compiler (nvcc) with the directive launch bounds.

Hardware view

When launching a kernel through programmer view concepts, the hardware will transpose these notions to hardware reality to fulfill its work.

Streaming Multiprocessor (SM)

A streaming Multiprocessor is the highest coarse-grained element in hardware. Each GPU consists of a group of SMs, which gathers all crucial resources needed to execute blocks of a grid, such as:

- Execution units:

- 128 CUDA cores for arithmetic operations,

- 32 special function units (SFUs) for single precision floating-point functions,

- …

- Caches:

- L1/Texture

- Constant (Read-only)

- Texture (Read-only)

- 4 warp schedulers,

- 32-bit registers (64K),

- …

The hardware assigns blocks to a SM according to available resources. Threads in a block will only run onto one and same SM. They will be able to communicate and synchronize through resources given by the SM. A SM has limited resources and that is why there is a maximum of active (resident) blocks per SM. This limit is 16 for a CC of 3.0 to 3.7, 32 for a CC of 5.0 to 7.0 and finally 16 resident blocks per SM for a CC of 7.5. When a SM executes a block, it executes all the inner threads entirely before executing the threads of another block.

Like blocks, the number of resident threads on a SM is limited (2048 on 6.2 CC). Thereby, block size will be taken into account to set the maximum of resident blocks per SM. For further details, the occupancy aspect has been studied by Vasily Volkov [3].

Warp

To fully use resources by a GPU, CUDA has introduced an abstraction which is an implicitly synchronized group of 32 threads called warp. The whole point of a warp is to exploit SIMT (Single Instruction Multiple Thread) architecture. A warp executes one common instruction at a time, with the possibility for threads to “mask” the instruction being executed, as in the case of conditional structures. Therefore, a warp is fully exploited when the same instruction is really executed (and not masked) by all the inner threads. The main parameters that can change between threads are those related to the thread ID (blockIdx.x, blockIdx.y, threadIdx.x, …). If threads of a warp diverge by a data-dependent conditional branch due to previously quoted parameters, the SIMT advantage is lost and the warp executes each branch path taken one by one, disabling threads that don’t belong to the chosen path.

Each block of threads is divided into warps. A warp contains threads of consecutive ID beginning with 0. As we launch a kernel code on a whole grid, threads within a warp are supposed to execute the same instruction at the same time. When a block is launched, it is considered active as long as all its warps haven’t been executed entirely. When a warp is assigned for execution, it will be distributed among SM’s inner warp schedulers. On any warp’s time issue (meaning doing nothing because of data dependencies or read/write operations), the execution context (registers, program counters, etc..) is maintained during the whole lifetime of the warp. This feature limits the available resources but offers a no cost switch context. During a warp’s time issue, the warp scheduler will select - if possible - one of its ready to execute assigned warps (a warp that contains active threads). Other warps can be launched by schedulers only if resources allow to do so. Allowed resident warps on a SM is limited to 64 on all CC except the 7.5 with a limitation of 32.

NB: Setting the number of threads per block as a multiple of 32 avoids wasting SM resources.

The image below summarizes the link between programmer view and how it is executed on hardware.

Warp also have their own id inside a block called warp ID (warpid). Then there is the coordinate of the thread in a warp: lane ID (laneid).

warpid = threadIdx.x / 32

laneid = threadIdx.x % 32

In a multi-dimensional block, as x is the major ordering, finding the warpid is about calculating multi-dimensional local ID and divide it by 32. For instance in a 2D block, warpid can be found by (blockDim.x*threadIdx.y + threadIdx.x)/32.

NB: Threads can directly access their laneid through a special register %laneid.

Memories

Memory holds an important place into CUDA programming. This chapter will be divided into two main parts. First we will introduce the memory hierarchy. It represents the associations between hardware concepts and associated memory segments. Then we will present one by one these memories and corresponding outline with a clear representation.

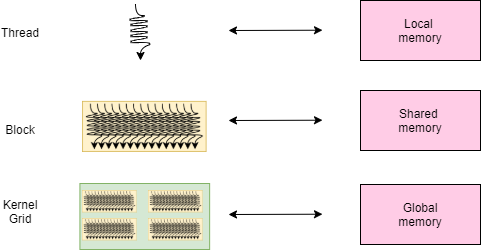

Memory hierarchy

In regard to the figure below, each thread has its own local memory and each block its own shared memory. For a grid, the global memory is the corresponding hierarchical memory but it’s not private. Furthermore, the global memory is accessible from all threads even from the host. Communication between enclosed concepts in the figure is expressed through depicted related memories. For example, threads within a same block can communicate through the dedicated shared memory. Also it is possible to launch multiple kernels and thus grids but overlapping won’t necessarily happen since resources are limited and one kernel will often “fill up” the whole GPU.

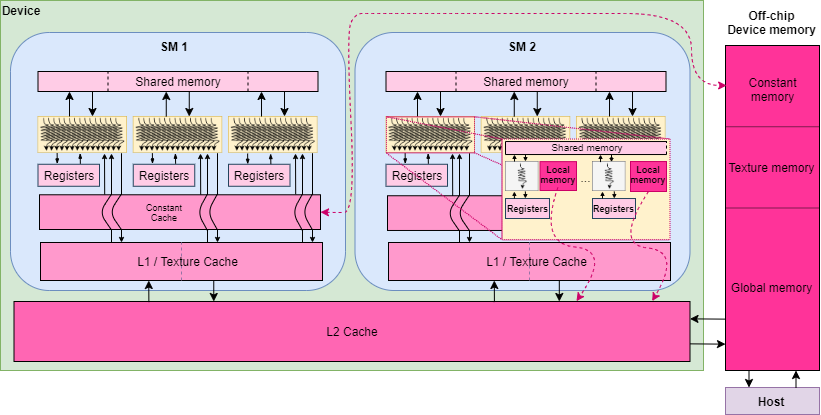

Memories and architecture

Before getting into details about each memory, a quick general look on GPU’s architecture focusing on memories is essential.

The above figure illustrates on the right side the off-chip device DRAM memory called simply device memory, holding the global memory and also the texture and constant memories. Accessing any of these memories will take the most amount of time comparing to on-chip memories. But constant and texture memories have on-chip caches. A constant cache is available in each SM and directly connected to its corresponding off-chip memory. Texture caches hold in the same place as each L1 caches, a logically divided space that can be partially tuned as cache behaviors. Thus, data misses on those caches could involve accessing the device memory and losing a lot of time.

To get deeper into memories, we will detail some aspect in a speed hierarchy approach beginning with the slowest one.

Global memory

The global memory is persistent through kernel calls. As it is in the device memory, we have a L2 cache shared by all SM that can store 524 KB to avoid to waste too much time. Furthermore, global memory can also use partially the 24 KB L1 cache of each SM to gain even more efficiency. Moreover, data being read-only for the entire kernel execution time can be detected by the compiler and therefore placed in the L1/texture cache. This placement is done by reading related data with the __lgd() function call. This function is used for data from which the compiler has detected the read-only property. Marking pointers with const or __restrict__ qualifiers can help the compiler detect this read-only property.

Global memory is a read and write - 8 GB memory on the Jetson TX2 - shared by the device and the host. It contains most of the needed data to the program (others are in the constant or the texture memories) and also the kernel code with a limit of 512 million instructions. Global memory can be accessed by any thread running on the device and even the host. It has a lifetime corresponding to the host allocation.

Local memory

Local memory is a private storage for an executing thread and a corresponding lifetime. According to Nvidia’s programming guide, local memory is accessed for some “automatic variables” that the compiler is expected to place in the local memoy. Those variables are:

- Arrays for which it cannot determine that they are indexed with constant quantities,

- Large structures or arrays that would consume too much register space,

- Any variable that brings register spilling.

For better performance, those variables can be stored by L1 or L2 caches depending of the device’s CC (device of CC 6.2 uses only the L2 cache). Also, the amount of local memory per thread is 512 KB for all CC.

Texture and surface memories

Initially dedicated to graphic uses, texture and surface memories (often just called texture memory) are among memories in the off-chip DRAM with a storage of 64 KB. The read-only texture memory has also a 24 KB on-chip cache shared with L1 caches. Those caches allow fast and efficient access with an optimized 2D spatial locality. Therefore, threads of the same warp reading texture or surface addresses that are close in a 2D perspective will achieve best performance. Texture memory can help when the reads don’t follow the access pattern needed for good performance with global or constant memory. It can also provide several other advantages like fast and low-precision linear interpolation of adjacent data values, automatic normalization of data and indices, etc…

Accessible as a read-only memory by all threads, it’s the host job to allocate and tranfer all data needed.

Constant memory

The constant memory is the last out-device memory, its 64 KB are used to store constant data - initialized by the host with a global scope and declared using __constant__ key word - during a whole kernel execution. It has a dedicated 8 KB cache inside all SM. Threads of a warp accessing a constant cache with different addresses will be serialized with a linear cost corresponding to the total number of unique addresses sent by the warp. The constant cache can be as fast as a register access if all threads within a warp access the same address.

Shared memory

Shared memory is present in each SM and is divided between resident blocks. On our Jetson TX2 we have 64 KB of shared memory per SM which is designed to be close to each SM’s processor. Each block can handle a maximum of 48 KB of shared memory. Therefore this memory avoids to cross all the way down to the device memory.

When the kernel code declares data for the shared memory, the compiler will create as many copies as resident blocks among SM. When a block is chosen to be executed, shared memory will be initialized for this block and be limited to the same block’s lifetime.

It is the only way to communicate and synchronize between all threads within the same block.

The shared memory works with 32 banks that are organized such that successive 32-bit words map to successive banks. Each bank has a bandwidth of 32 bits per clock cycle an can be accessed simultaneously, achieving in total an effective bandwidth as high as the accessed banks times the bandwidth of a single one of them. Accessing the shared memory can be as fast as accessing registers.

However, if multiple addresses of a memory request map to the same memory bank, those accesses are serialized. The hardware will then split the memory request that has created bank conflicts into as many separate conflict-free requests as necessary, dividing the throughput by the number of separate memory requests. The only exception here is when multiple threads in a warp address the same shared memory location, resulting in a broadcast. In this case, multiple broadcasts from different banks are coalesced into a single multicast from the requested shared memory locations to the threads [4].

Registers and shuffle

Registers are private on a thread level. A thread can have a maximum of 255 registers but the compiler heuristically allocates registers to each thread in order to both maximize parallelism and minimize spilling according to the kernel code. When spilling occurs, the L2 cache for 6.2 CC can help with data request hit. Caches behavior depends of the CC and also on the partial possible configuration offered.

With warp’s regroupment, CUDA has introduced in all CC a new warp level concept working on registers called shuffle. Shuffle (SHFL) is a set of instructions for exchanging data between threads of the same warp by “reading” other threads’ registers. Shuffle can ease the shared memory of some data and thus help a lot with applications where performance depends on available shared memory.

References

[1] Wccftech.com, NVIDIA GeForce GPUs Strike Hard At AMD’s Radeon In The Discrete DIY Market – Green Team Share Climbs 5% As AMD Share Falls Below 30% In Q3 2019, Nov 2019.

[2] Xingliang Wang, Xiaochao Li, Mei Zou and Jun Zhou, “AES finalists implementation for GPU and multi-core CPU based on OpenCL,” 2011 IEEE International Conference on Anti-Counterfeiting, Security and Identification, Xiamen, 2011, pp. 38-42.

[3] Vasily Volkov, Better Performance at Lower Occupancy, UC Berkely, Sept 2010.

[4] Nvidia, CUDA C++ Best Practices Guide, Nov 2019.

[5] Nvidia, CUDA C++ Programming Guide v10.2.89, Nov 2019.